MaitriMind Blog

1/11/2021

Benefits of Practicing Mindfulness as a Family

Mindfulness is increasingly common in classrooms as an intervention strategy, part of the rhythm of the day, or even as a teaching pedagogy, but even long before children start school, they can benefit from mindfulness. In fact, the whole family can improve physical, mental, and emotional health by practicing together. Additionally, the family unit gains compassion, increased communication skills, and a shared vocabulary for conflict resolution when a solid foundation of mindfulness is present. Perhaps the most joyous benefit of practicing mindfulness as a family is the happy memories made together when everyone is fully present and in tune with each other.

Parents often ask when the best time is to start mindfulness with their children. Ideally, it would be before they are even born, yet it is never too late to start! According to Greater Good Magazine, participants in Nurse-midwife Nancy Bardacke’s Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting (MBCP) classes reported improvements in pregnancy anxiety and stress levels and more frequent positive feelings—such as enjoyment, gratitude, and hope—after the program. The breathing exercises that are the foundation of Lamaze birthing and pain-management strategies are identical to some of those used in mindfulness. I can personally verify that having an established meditation practice made patience and flexibility much easier in my parenting. On the other hand, whether your child is in pre-school, elementary, middle, or high school, there are mindfulness practices and curricula for their age group that facilitate developmental milestones and ease the specific challenges for each age-group.

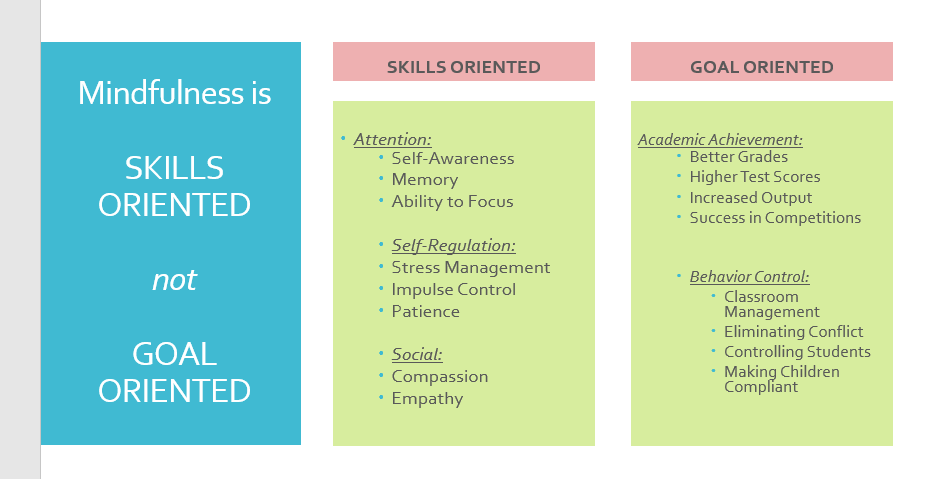

No matter what age is your entry point to mindfulness practices (even adulthood), to effectively achieve the physical, mental, and emotional benefits, it is important to understand that mindfulness is skills-oriented, not goal-oriented. For example, a reasonable physical intention would be to meditate for 5-10 minutes per day for at least six weeks. That is the length of time necessary to begin to activate neuroplasticity and rewire your brain to respond instead of react to situations. Just like any health plan, focusing on strategies instead of results is more realistic. It is also more fair to focus on skills instead of goals with the mental and emotional aspects of mindfulness with children of any age. The following table shows the subtle differences in motivation and integrity of mindfulness teaching when this principal is remembered.

A wonderful part of practicing mindfulness as a family is the social-emotional bonding and shared strategies for communication that each member of the group gains. While having a goal of no bickering in the family is not realistic, it can be lessened when each person has the same problem-solving toolkit. Even the youngest children can remember to pause and take deep breaths, go gather their thoughts in a Peace Place, or do some physical activity when big feelings are threatening to take over. It is a beautiful thing to see children support each other and the adults in their lives by suggesting mindful strategies to a family member in distress! Classes in engaged mindfulness from The School of Mindful Arts also cover such conflict resolution strategies as justice circles, using “I” statements, deep listening, Native American inspired talking sticks, and a game called Grok cards. (https://www.groktheworld.com/kids-grok)

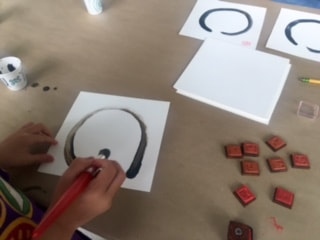

In my parenting journey, the thing I have most appreciated about weaving mindfulness into the fabric of our family life has been the shared memories we have made. The definition of mindfulness is “being aware, in the present moment, without harmful negative judgements”. This quality of being fully present to my family and each individual moment we are sharing extends beyond the dedicated mindfulness practice sessions to an appreciation of all our times together. While some of my favorite memories with my children have been taking mindful walks/nature hikes, doing contemplative arts and crafts together, and engaging in more formal meditation practices, the quality of mindful presence has enabled me to appreciate and treasure the more mundane elements of family life- even doing chores together. Embracing the value of non-judgement can even make each family member more likely to try new activities that they may not initially feel drawn to.

Being gentle with yourself and your family without unrealistic expectations is the basis for both living mindfully and starting to implement formal mindfulness practices into the rhythm of your days. Mindfulness is a process and way of being as much as a set of exercises and practices. Both formal and informal mindfulness have important places in family life, no matter the age of your children. So, you can decide to implement sitting together with an auditory focus of nature sounds for five minutes before bed every night AND slow down and walk in silence listening to the birds in an impromptu way when hiking. You can do yoga together regularly AND use tree pose as a strategy for grounding when upset. There are many tools and resources available to support parents in raising a mindful family. The most important part is to find your own entry point, no matter the age of your children or your previous level of experience and give mindfulness a try!

Parents often ask when the best time is to start mindfulness with their children. Ideally, it would be before they are even born, yet it is never too late to start! According to Greater Good Magazine, participants in Nurse-midwife Nancy Bardacke’s Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting (MBCP) classes reported improvements in pregnancy anxiety and stress levels and more frequent positive feelings—such as enjoyment, gratitude, and hope—after the program. The breathing exercises that are the foundation of Lamaze birthing and pain-management strategies are identical to some of those used in mindfulness. I can personally verify that having an established meditation practice made patience and flexibility much easier in my parenting. On the other hand, whether your child is in pre-school, elementary, middle, or high school, there are mindfulness practices and curricula for their age group that facilitate developmental milestones and ease the specific challenges for each age-group.

No matter what age is your entry point to mindfulness practices (even adulthood), to effectively achieve the physical, mental, and emotional benefits, it is important to understand that mindfulness is skills-oriented, not goal-oriented. For example, a reasonable physical intention would be to meditate for 5-10 minutes per day for at least six weeks. That is the length of time necessary to begin to activate neuroplasticity and rewire your brain to respond instead of react to situations. Just like any health plan, focusing on strategies instead of results is more realistic. It is also more fair to focus on skills instead of goals with the mental and emotional aspects of mindfulness with children of any age. The following table shows the subtle differences in motivation and integrity of mindfulness teaching when this principal is remembered.

A wonderful part of practicing mindfulness as a family is the social-emotional bonding and shared strategies for communication that each member of the group gains. While having a goal of no bickering in the family is not realistic, it can be lessened when each person has the same problem-solving toolkit. Even the youngest children can remember to pause and take deep breaths, go gather their thoughts in a Peace Place, or do some physical activity when big feelings are threatening to take over. It is a beautiful thing to see children support each other and the adults in their lives by suggesting mindful strategies to a family member in distress! Classes in engaged mindfulness from The School of Mindful Arts also cover such conflict resolution strategies as justice circles, using “I” statements, deep listening, Native American inspired talking sticks, and a game called Grok cards. (https://www.groktheworld.com/kids-grok)

In my parenting journey, the thing I have most appreciated about weaving mindfulness into the fabric of our family life has been the shared memories we have made. The definition of mindfulness is “being aware, in the present moment, without harmful negative judgements”. This quality of being fully present to my family and each individual moment we are sharing extends beyond the dedicated mindfulness practice sessions to an appreciation of all our times together. While some of my favorite memories with my children have been taking mindful walks/nature hikes, doing contemplative arts and crafts together, and engaging in more formal meditation practices, the quality of mindful presence has enabled me to appreciate and treasure the more mundane elements of family life- even doing chores together. Embracing the value of non-judgement can even make each family member more likely to try new activities that they may not initially feel drawn to.

Being gentle with yourself and your family without unrealistic expectations is the basis for both living mindfully and starting to implement formal mindfulness practices into the rhythm of your days. Mindfulness is a process and way of being as much as a set of exercises and practices. Both formal and informal mindfulness have important places in family life, no matter the age of your children. So, you can decide to implement sitting together with an auditory focus of nature sounds for five minutes before bed every night AND slow down and walk in silence listening to the birds in an impromptu way when hiking. You can do yoga together regularly AND use tree pose as a strategy for grounding when upset. There are many tools and resources available to support parents in raising a mindful family. The most important part is to find your own entry point, no matter the age of your children or your previous level of experience and give mindfulness a try!

|

11/16/2020

|

The Symbiotic Relationship

Between Mindfulness and Environmental Education

Environmental studies, ecology, and conservation as we know them today were disciplines which gained momentum in the 1960s. They were largely inspired Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, but philosophers and scientists including Rousseau, Darwin, Thoreau, and Aristotle all laid the groundwork for these fields hundreds of years before. Similarly, Jon Kabat-Zinn coined the term “mindfulness” in 1979, but every religion for thousands of years prior had contemplative practices. Combining education in these two fields has become increasingly common in the past ten years, but from the start of the nature education movement in the 19th century the spiritual and ethical aspects of humans in their environment was emphasized. Recent research has shown that people who combine mindfulness and environmental studies reap benefits for their individual physical, emotional and cognitive health. These same cognitive gains also support social and global changes and implementation of sustainability initiatives, so using the terminology of biology, they are mutually beneficial, symbiotic disciplines.

On an individual level, there are many potential health benefits from practicing mindfulness in nature. Because movement is usually involved in outdoor contemplative activities, yoga and tai chi for example, practitioners get the physical benefits of exercise in addition to the mental/emotional supports of the mindfulness process. Choosing to practice mindfulness outdoors also gives one the ability to try specific mindfulness practices which are only done in nature, such as forest bathing and walking meditation. The clinical mindfulness benefits of reduced blood pressure, increased immunity, deeper sleep, etc. are improved when combined with gentle exercise. Provided you are in an area with good air quality, the healthy outcomes of breathing exercises and increased oxygen in the body are boosted by practicing outdoors in the fresh air.

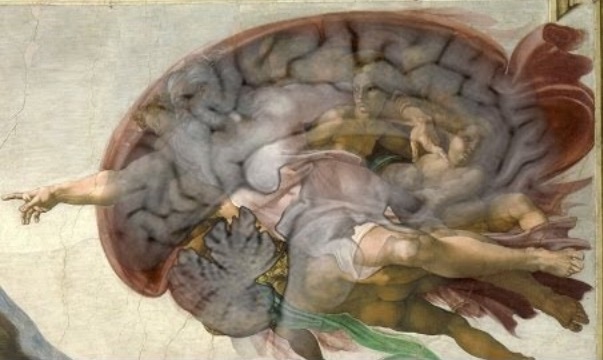

Children and adults alike also benefit physically from mindfulness due to neuroplasticity, the ability of the brain to continually reorganize itself and grow. Contemplative practices build the neural connections between the amygdala, the primal part of the brain, and the prefrontal cortex, the seat of higher reasoning. Positive neuroplasticity promotes emotional regulation which supports many of the

goals of environmental education. Mindfulness gives people an increased sense of well-being which helps them to feel more optimistic about environmental problems. The awareness of interdependence gained from contemplative practices builds feelings of connection to the natural world, thus increasing individuals’ desire to care for the planet. Likewise, heightened compassion increases concern for equity and justice for others, encouraging a sustainability mind-set. Emotional resilience is one of the most important outcomes from mindfulness practices, and this quality promotes the confidence to act instead of feeling overwhelmed about climate change and other environmental concerns.

Combining mindfulness practices with environmental education builds cognitive as well as emotional skills which contribute to a deeper understanding of sustainability and an improved ability to be a change-maker. Learning how to pause and take a breath and knowing how to respond instead of react to situations enables more skillful and peaceful advocacy. Cultivation of the core values which are part of ethical mindfulness education activates a sense of responsibility for others, communities, and the planet. The increased density of the pre-frontal cortex which comes from sustained mindfulness practice promotes better problem-solving skills and leads to increased innovation in mitigation strategies for environmental threats and disasters.

A more recent sub-discipline of secular mindfulness is engaged mindfulness which is usually begun after an individual has a solidly established personal practice. This practice is more in keeping with the original term of Right Mindfulness from Buddhist philosophy. Engaged mindfulness seeks to integrate social and scientific knowledge with empathy and values to inspire involvement and action. I explain engaged mindfulness to children with the metaphor of helping others as well as oneself being as crucial as breathing out as well as breathing in. Since our first mindfulness lessons are establishing awareness of the breath, focusing on exhaling along with inhaling is an image that they are prepared to understand as their practice matures. Engaged mindfulness promotes environmental activism by imparting a feeling of belonging to one human family sharing one planet. One of the most beautiful ways engaged mindfulness practice prepares children to be citizens of the world, especially when combined with environmental education, is by developing an appreciation of indigenous wisdom and relationship native peoples have with nature.

In my upper level lessons for teens and adults, I make a distinction between engaged mindfulness and applied mindfulness, with the latter having an even broader scope and the goal of addressing systemic changes beyond just the call for individual activism. The new neural connections built over time with even short sessions of meditation repeated often facilitate a growth-mindset and empower practitioners with the ability to devise new structures and frameworks. The group altruism developed by being a part of a mindful community fosters a desire for social, economic, and political equity. Any initiatives to promote true social sustainability also have positive effects on the environment

by reducing consumption and waste. Part of being trained as an engaged mindfulness educator includes learning about trauma and restorative practices, as meditation and other contemplative practices are often used as supports in mental health interventions. This understanding of trauma and healing is also often applied to using mindfulness strategies to victims of natural disasters. Being a part of a mindful community promotes a commitment to contribute towards deep, lasting comprehensive changes.

From individual health, emotional, and cognitive benefits to improvements in the well-being of communities and the planet, practicing mindfulness and environmental education together offers improved outcomes in many areas. The fields support each other, and together support individuals with the worldview and skills to make true change. Mindfulness teaches the resilience to be with personal, environmental, and social problems and the confidence to find and implement solutions. The mindfulness lessons in communication and conflict resolution empower students with the tools to be peaceful, skillful advocates. Mindfulness practices often have enhanced benefits for people when done outside. Environmental advocates who have mindfulness trainings gain coping strategies for being with the anxieties of climate change, and therapeutic tools to help victims of natural disasters. The practices of both engaged and applied mindfulness specifically encourage individuals to feel connected to others and the natural world and thus contribute to caring for the well-being of communities and the planet. Mindfulness and contemplative studies, sustainability and environmental studies are inherently symbiotic and people of all ages benefit greatly from being taught both disciplines together.

On an individual level, there are many potential health benefits from practicing mindfulness in nature. Because movement is usually involved in outdoor contemplative activities, yoga and tai chi for example, practitioners get the physical benefits of exercise in addition to the mental/emotional supports of the mindfulness process. Choosing to practice mindfulness outdoors also gives one the ability to try specific mindfulness practices which are only done in nature, such as forest bathing and walking meditation. The clinical mindfulness benefits of reduced blood pressure, increased immunity, deeper sleep, etc. are improved when combined with gentle exercise. Provided you are in an area with good air quality, the healthy outcomes of breathing exercises and increased oxygen in the body are boosted by practicing outdoors in the fresh air.

Children and adults alike also benefit physically from mindfulness due to neuroplasticity, the ability of the brain to continually reorganize itself and grow. Contemplative practices build the neural connections between the amygdala, the primal part of the brain, and the prefrontal cortex, the seat of higher reasoning. Positive neuroplasticity promotes emotional regulation which supports many of the

goals of environmental education. Mindfulness gives people an increased sense of well-being which helps them to feel more optimistic about environmental problems. The awareness of interdependence gained from contemplative practices builds feelings of connection to the natural world, thus increasing individuals’ desire to care for the planet. Likewise, heightened compassion increases concern for equity and justice for others, encouraging a sustainability mind-set. Emotional resilience is one of the most important outcomes from mindfulness practices, and this quality promotes the confidence to act instead of feeling overwhelmed about climate change and other environmental concerns.

Combining mindfulness practices with environmental education builds cognitive as well as emotional skills which contribute to a deeper understanding of sustainability and an improved ability to be a change-maker. Learning how to pause and take a breath and knowing how to respond instead of react to situations enables more skillful and peaceful advocacy. Cultivation of the core values which are part of ethical mindfulness education activates a sense of responsibility for others, communities, and the planet. The increased density of the pre-frontal cortex which comes from sustained mindfulness practice promotes better problem-solving skills and leads to increased innovation in mitigation strategies for environmental threats and disasters.

A more recent sub-discipline of secular mindfulness is engaged mindfulness which is usually begun after an individual has a solidly established personal practice. This practice is more in keeping with the original term of Right Mindfulness from Buddhist philosophy. Engaged mindfulness seeks to integrate social and scientific knowledge with empathy and values to inspire involvement and action. I explain engaged mindfulness to children with the metaphor of helping others as well as oneself being as crucial as breathing out as well as breathing in. Since our first mindfulness lessons are establishing awareness of the breath, focusing on exhaling along with inhaling is an image that they are prepared to understand as their practice matures. Engaged mindfulness promotes environmental activism by imparting a feeling of belonging to one human family sharing one planet. One of the most beautiful ways engaged mindfulness practice prepares children to be citizens of the world, especially when combined with environmental education, is by developing an appreciation of indigenous wisdom and relationship native peoples have with nature.

In my upper level lessons for teens and adults, I make a distinction between engaged mindfulness and applied mindfulness, with the latter having an even broader scope and the goal of addressing systemic changes beyond just the call for individual activism. The new neural connections built over time with even short sessions of meditation repeated often facilitate a growth-mindset and empower practitioners with the ability to devise new structures and frameworks. The group altruism developed by being a part of a mindful community fosters a desire for social, economic, and political equity. Any initiatives to promote true social sustainability also have positive effects on the environment

by reducing consumption and waste. Part of being trained as an engaged mindfulness educator includes learning about trauma and restorative practices, as meditation and other contemplative practices are often used as supports in mental health interventions. This understanding of trauma and healing is also often applied to using mindfulness strategies to victims of natural disasters. Being a part of a mindful community promotes a commitment to contribute towards deep, lasting comprehensive changes.

From individual health, emotional, and cognitive benefits to improvements in the well-being of communities and the planet, practicing mindfulness and environmental education together offers improved outcomes in many areas. The fields support each other, and together support individuals with the worldview and skills to make true change. Mindfulness teaches the resilience to be with personal, environmental, and social problems and the confidence to find and implement solutions. The mindfulness lessons in communication and conflict resolution empower students with the tools to be peaceful, skillful advocates. Mindfulness practices often have enhanced benefits for people when done outside. Environmental advocates who have mindfulness trainings gain coping strategies for being with the anxieties of climate change, and therapeutic tools to help victims of natural disasters. The practices of both engaged and applied mindfulness specifically encourage individuals to feel connected to others and the natural world and thus contribute to caring for the well-being of communities and the planet. Mindfulness and contemplative studies, sustainability and environmental studies are inherently symbiotic and people of all ages benefit greatly from being taught both disciplines together.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed